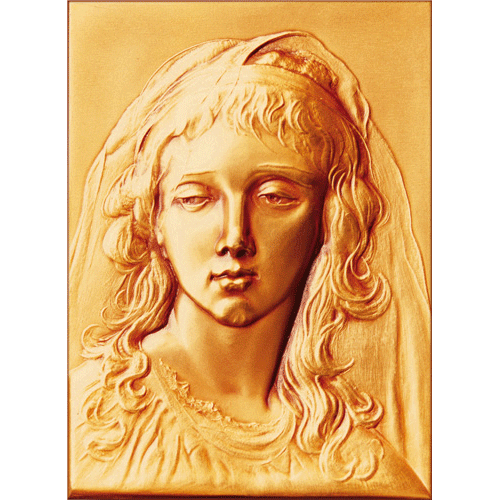

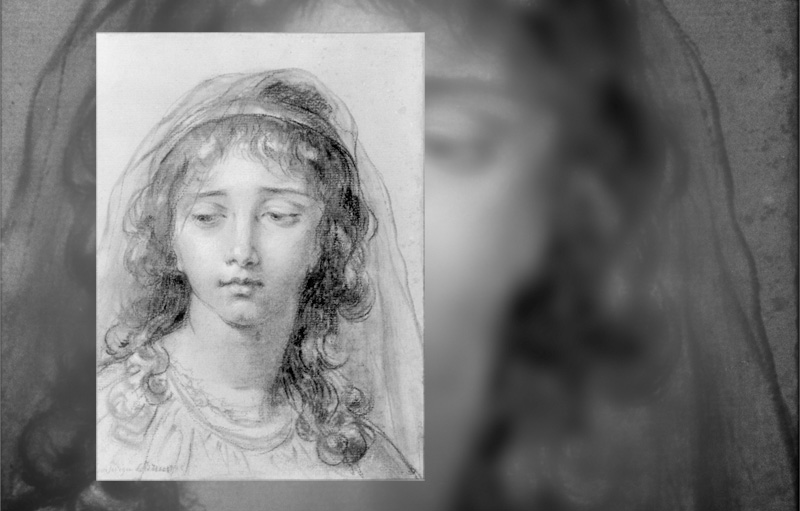

1 – MANDATORY SUBJECT:

Based on the drawing of Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, « A young girl’s face », make with a punch or a die a direct steel carving of this subject for the purpose of striking a medal.

RESEARCH ABOUT THE SUBJECT.

In order to get into the subject, I had to carry out a few approach tasks. I needed to improve my knowledge about the painter and her works, so that I could better understand her style and her sensibility. A few works from the 18th century also helped me to grasp the prevailing trends of that time (clothing, hairstyle…) and the way artists used to sculpt a face, a bust.

Left: Elisabeth VIGÉE-LEBRUN (1758-1842)

Official painter for the Queen Marie-Antoinette.

THE « DIRECT CARVING » ENGRAVING

In light of the previous steps, I get straight to the heart of the matter : the « direct carving ».

– Copy of the drawing on a gelatin at scale 1 : 65 mm x 87 mm.

– Light engraving with an onglette (sharp and round). That was the beginning of a lengthy task.

– Then, the set up of the broad volumes. I carry on the long and tedious direct carving work, in order to make the various volumes complement one another. Throughout this work, I’ve used resin prints to record the various steps so that I could track the engraving development.

– Making of a punch of the nose and the mouth. Quenching and sinking of it inside the die. Annealing of the die after the sinking in order to remove the hardening caused by the punch strike. Then, the die engraving goes on. I had to soften the lips, its edges being too sharp, for the mouth is a round flesh volume fading out around the corners of the lips.

– Finishing stage of the engraving by setting various surface conditions, in order to convey the matters (veil, face, hair, etc.) – by polishing, chiselling…

– Heat treatment: material : Z50CWDV5 – SMV5W – Weight: 10 kg – Hardness 59-60HRC.

– Stamping and finishing of the 3 medals: the striking of the medals was performed by a 400-ton friction « balancier ». We used copper and « semi-red » bronze. A dozen of passes were necessary and between each one : annealing, « déroché », polishing and degreasing were carried out. The medals were struck in three copies : two made of golden bronze with old gold finish, and one made of copper without patina to showcase the quality of the engraving.

THOUGHTS

Though difficult, I was motivated by the richness of this subject throughout its making. I’ve been immediately fascinated by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s drawing – an artist I discovered at the same time. Shaping her light and subtle drawing of a young girl’s face was a great and demanding challenge.

Working « the old-fashioned way » and rediscovering the feeling of being as one with the material was also very motivating.

It allowed me to meet old engravers who were proficient in the direct carving technique, and by doing so I compensated for the too common and saddening lack of transmission of knowledge in our trade.

Many thanks to Mr Bernard Turland, former master engraver from La Monnaie de Paris, whom I learned so much from, and Mr Claude Gardot, MOF steel engraver.

2 – OPEN SUBJECT:

Creation of a medal based on one of the Labours of Hercules.

RESEARCH ABOUT THE SUBJECT

Selection of the Nemean Lion

In my opinion, the Nemean Lion is the greatest of the Labours of Hercules ; it symbolizes the hero’s strength, power and courage.

Hercules was required to find the lion which terrorized the region surrounding Nemea. When he eventually found himself opposite the beast, he shoot his bow and arrows against it but none of them could pierce the monster’s skin. Le lion ran away but Hercules followed it to a cave where he fought it and choked it to death with his mighty arms. He skinned the beast and made himself a coat with the thick skin.

Depictions of Hercules during Antiquity. He is almost always wearing the lion skin, his head covered with the beast’s open mouth. He has a short beard and is always depicted as a muscled athlete. His weapons and attributes differ depending on his ennemies : most often a club and a bow, but also a sword in a silver sheath, given by Mercury ; a sickle to chop the Hydra’s heads off ; a sling against the Stymphalian birds ; sometimes he sports a golden body armor forged by Vulcan.

Among the Labours, the Nemean Lion is the most frequently represented, in particular on Attic ceramic. It also appears on the coins of Heraclea, a city from Lucamia (5th century BC).

ICONOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

In order to design my medal about one of the Labours of Hercules, I looked at how artists have been dealing with the subject – be it through drawings, engravings or sculptures. Second, I carried out some personal research about judokas to review fighting attitudes with strangulation techniques which would convey strength and motion.

1 – Various coins:

Syracuse – probably engraved by Evainete – Gold coin – around 400 BC.

City of Lebee Island – Carysttus – beginning of the 2nd century BC.

City of Thasos – Silver coin – End of the 2nd century BC.

Heraclea – Silver coin – 3rd century BC.

Coin, obverse and reverse

City of Croton – Silver coin – 3rd century BC.

2 – Drawings, paintings and comics: Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. I’ve also drawn my inspiration from comic artist Burne Hogarth’s drawings of Tarzan fighting lions and wild animals.

3 – Sculptures :

The lions of A. L. Bary, a sculptor who made bronze pieces and plaster studies which can be seen in the Louvre Museum. Other sculptors – such as Cain in particular – have also greatly influenced my work.

Michel Anguier (1614-1686) : Hercules helping Atlas & Nicolas Coustou (1658-1733) : Hercules Commode.

A Sumerian bas-relief struck me because of an unusual composition : there was a very tiny lion and an oversized Gilgamesh (the Sumerian Hercules), symbol of power and divine sonship.

4 – Photographs of judokas: two fighting judokas working on strangulation and neck-locks techniques.

COMPOSITION OF THE MEDAL

Strength and power were the main areas of my research. I’ve looked for ways to bring out these focuses and I studied some compositions for a long time. Therefore, I did a lot of drawings on tracing paper (that medium made it possible to entangle various postures) and scanned them. They were then retouched, edited and transformed several times. This allowed me to get the final composition done.

MAKING OF THE MEDAL

Sculpture: when all the research and sketching steps were over, I started the clay modeling from my final drawing. This enabled a quick and lively setting up at scale 3. Then I made a plaster print to carry out some corrections, add some material where needed… and so on : moulding, counter-moulding, adjustments…

Eventually, 1 clay moulding, 4 counter-mouldings and 4 prints were needed to complete my carved project. Throughout the creation, I tried to surround myself with other craftsmen such as sculptors, designers, engravers, etc. who could question my views.

New engraving technologies:

I submitted my project to several companies :

– Vision numérique (engraving software development in two or three dimensions)

– The Remishaw company for mechanical probing

– The Alltec company for laser machining

I carried out several attempts but none of them has proven to be satisfactory.

The traditional way

Eventually, I chose to downsize my sculpture with a pantograph. Indeed, this machining technique allows me to work on the pieces with greater flexibility, better control and precision, throughout the making.

– Hand finishing the engraving : when hand finishing, I put the last touches to the making of the medal. I also work on the materials (lion hair, soil, background…) and any machining mark is removed.

– Heat treatment : material : Z50CWDV5 – SMV5W – Weight: 10 kg – Hardness 59-60HRC.

– Stamping : the striking of the medals was performed by a 400-ton friction « balancier ». We used copper and « semi-red » bronze. A dozen of passes were necessary and between each one : annealing, « déroché », polishing and degreasing were carried out.

The Hercules medals were sized with a turning machine. Diameter 84 mm, struck in three copies : two made of golden bronze with old gold finish, and one made of copper without patina to showcase the quality of the engraving.

THOUGHTS AND CONCLUSION

I’ve been so busy with the engraving of the young girl’s face that I found it hard to get into the subject of the Nemean Lion.

It has been an interesting and motivating creative work. I enjoyed being immersed in the world of the new engraving techniques, trying out to identify the pros and cons of each one. After I thought about these new options, I decided to return to the traditional methods ; even if slower, they allow me to keep some closeness with the work in progress.

Furthermore, the creative work have led me to develop ties with craftsmen from diverse backgrounds. These contacts between crafts were highly rewarding for everyone involved have been providing guidance until the project was completed.

In conclusion, I found both projects very exciting. Because of their richness and complexity, new fine details arose at each stage of the process. That’s the reason why it has been so difficult for me to complete these tasks. When creating an engraved piece, one feels that there’s always room for further progress. However, the decision to end the making is both frustrating and regenerating!